by Kathleen Cason

Intro

| Revolution and Abolition

| Widening the Canon

| Found in Translation

Widening the Canon

Kadish’s academic career began with a dissertation on the French New Novelist Claude Simon, who later won the Nobel Prize in literature, mainly because his work — in contrast to that of most New Novelists — dealt with social issues. That appealed to Kadish.

“In absolutely everything I’ve ever published is that element of social change and social justice,” Kadish said. “That has been with me my whole life.”

Kadish’s mother, born in Savannah, Ga., in 1908, was herself a socially conscious person who despised racism. At age 19 and fresh out of high school, she hopped a bus to New York City, where she would meet and marry Kadish’s father. His family had emigrated from Russia after losing the family-owned bookbindery, and everything else, during the Russian Revolution. He held to the belief that all cultured people should learn French.

Discussions of the day’s public issues were common fare at dinnertime. Her parents, while sympathetic to human rights and social causes, were fatalistic — skeptical that change was possible. Kadish, however, argued for and believed in social change. As a student during the 1960s, she didn’t take to the streets but quietly contributed to social causes through scholarship.

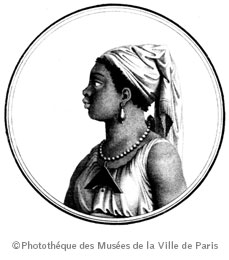

This illustration from a history of the Haitian slave revolts shows the burning of Le Cap, Haiti, and massacre of whites. While this book focused on the violence of the Haitian slave revolt, UGA French Professor Doris Kadish discovered that literature by 19th-century women took a more modern view — that the violence arose out of inhumane conditions and cruelties under slavery. Incendie du Cap. Révolte générale des Nègres. Massacre des Blancs. Frontispiece from the book Saint-Domingue, ou Histoire de Ses Révolutions. ca. 1815. Paris: Chez Tiger.

When she arrived at UGA in 1993 to head the Romance Language Department, Kadish already had a keen interest in the issue of slavery and abolitionism in French literature. She had studied and admired a seminal work by Léon-François Hoffmann, a professor of French at Princeton University, but realized that he and most other scholars seemed to overlook writings by women.

They overlooked something else as well. “Hoffman’s book had made a considerable impact, but it did not force the study of francophone slavery to the center of attention. It remained essentially marginal,” said Roger Little, professor emeritus and former chair of French at Trinity College, Dublin.

But that started to change after publication of Kadish’s and Massardier- Kenney’s Translating Slavery. This well-received and much-discussed book examined writings on race and gender by three French women. In addition, it analyzed how their works were translated and the factors that influenced translation.

“The translator’s job is to get out of the way and let the original voice speak,” Little said. But Kadish and the book’s other contributors discovered that when it comes to charged subjects like race and slavery, translators do not get out of the way. Many factors — racial background, gender, ideology, culture — affect the translation. “A word that might be offensive to use now might not be offensive at all at the time and might actually be used by people who were abolitionists,” Massardier-Kenney said. “You have to study how those words would be used in English not only now but at the time when the story takes place.”

One example is the word black. “That word is loaded,” Kadish said. “In French, noir was used by abolitionists; nègre was used by others, but it has negative connotations.” The translation must reflect this.

Following the success of Translating Slavery, Kadish hosted international conferences at UGA. “Doris has been a pioneer in this whole area,” said Deborah Jenson, associate professor of French at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “In 1997, when she put on two simultaneous symposia at the University of Georgia — the 19th-Century French Studies conference and the Slavery in the Francophone World conference — that was the first time that 19th-century French scholars had been organized around issues of slavery, colonialism and post-colonialism.”

One of the conferences’ highlights was the first English-language production of Caribbean-born Maryse Condé’s play In the Time of the Revolution, which is about the slave revolts in Haiti and Guadeloupe. The conferences also were the impetus for a book of essays about forgotten events and repercussions of slavery on France, former French colonies and the United States. Slavery in the Caribbean Francophone World: Distant Voices, Forgotten Acts, Forged Identities, published in 2000 and edited by Kadish, included essays by contributors from disciplines such as history, literature, linguistics and journalism.

“Doris Kadish has widened the canon of 19th-century French studies and she has looked at it from the angle of other disciplines and cultural studies,” Massardier- Kenney said.

Intro

| Revolution and Abolition

| Widening the Canon

| Found in Translation

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()