Hubert McAlexander chronicles the lives, times and works of two Southern authors

by Kathleen Cason

Intro

| A Mississippi lady |

Writing a writer's life

|

Patience and Fortitude

Katharine Sherwood Bonner McDowell (1849-1883) fled Mississippi to pursue her writing career in Boston where she mingled with Boston's upper crust. "Her life was a much better story than anything she wrote," said biographer Hubert McAlexander.

After

Bonner's death, her friend and admirer, General Colton Greene, purchased

Cedarhurst, her family home in Holly Springs, Miss., and deeded it to

Bonner's daughter, Lilian.

A Mississippi lady

"Sherwood Bonner was just so dramatic and fascinating and so self-dramatizing and vain," McAlexander said. "Her life was a much better story than anything she wrote."

Although her writing left no indelible mark, McAlexander said her biography is valuable, in part, because what she wrote was widely representative of her time.

"Minor figures provide a wonderful index of an era, sometimes more than the major ones, because major people are often atypical," he said.

McAlexander's book, The Prodigal Daughter: A Biography of Sherwood Bonner, renders a sympathetic portrayal of an intellectual young woman's struggle to realize her dream to be a writer. Her brief but dramatic life is a window on life in Mississippi and Brahmin Boston during and after the Civil War.

Katharine Sherwood Bonner McDowell was born in 1849 in McAlexander's hometown of Holly Springs, Miss., at the time a prosperous town in the state's leading cotton producing county. At age 13, Bonner's father sent her to Montgomery, Ala., to escape the war. But after barely six months, she returned home to a town that was unrecognizable — razed buildings, toppled gravestones and defaced houses. McAlexander wrote that she traveled "a ruined countryside back to Holly Springs," the last leg of the trip on a "handcar operated by a blind man, a cripple and two former slaves."

Following the war, the 22-year-old Bonner married a dreamer who was never much of a husband. A year and a half into the marriage, he left Mississippi to seek his fortune in Texas. Bonner and their infant daughter joined him briefly but she soon decided she had had enough. She returned to Holly Springs, left her young daughter in her mother-in-law's care and headed for Boston to pursue her education and a career as a writer — bold, scandalous behavior for the times.

She eked out a living by selling stories to various magazines and newspapers and by working as a secretary to temperance advocate and physician Dio Lewis and later to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. She wrote in the grandiloquent style of the times and achieved only modest success.

McAlexander didn't have much to go on for the Bonner biography. Only about a hundred letters remained and Bonner had been dead for more than a century. Many of her works were missing. No one who had known her was still alive.

"My art teacher had been in a Shakespeare class that Sherwood Bonner's daughter gave for young children in the 1880s," he said. "I almost touched her but not quite."

So McAlexander had to be particularly ingenious in his research. He scoured archives, libraries and private collections for clues — diaries, correspondence, deeds, court proceedings, journals, obituaries, family Bibles, contracts, tuition bills, scrapbooks and even cancelled checks.

Rummaging through the collections at the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Boston Athenæum and Harvard's Houghton Library, he unearthed Bonner's first published work, which had been "lost" since 1898.

"She told people her first work was published when she was 15 years old. After looking at some diary entries, I was pretty sure that was not right," he said. "I really thought she was published first when she was 20 and I knew it was in some Boston publication. So I went to Boston on this hunch. At the Boston Public Library I got hold of these obscure magazines way down in the sub-basement, just hidden away, and there her first story was."

He uncovered other long-forgotten stories in the Memphis Avalanche. The editor was Bonner's friend and published many of her articles — impressions of life in Boston and Europe, sketches of prominent Bostonians such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Wendell Phillips, and events such as the funeral of abolitionist Charles Sumner and Boston's centennial celebration. But a painstaking hunt through 10-year's worth of the Avalanche turned up a bigger find — Bonner's connection with social reformer Elizabeth Avery Meriwether.

Bonner most admired this "woman of intellect, force, and independence, who, at the same time displayed femininity and style," McAlexander wrote. Meriwether, like many of Bonner's female friends, possessed these qualities — intellect combined with femininity — that embodied emerging Southern feminism.

Hard-earned scraps of information surfaced in unexpected places. McAlexander discovered a draft of Bonner's letter to her literary adviser, Nahum Capen, on the back of a manuscript in her grandnephew's possession. In a previous letter to Capen, she divulged her plans to go to Boston; his reply voiced outrage that she would leave her child behind. This draft responded to his censure, defending her decision and her dreams.

"The draft was too haughty,"McAlexander wrote, "and she probably sent a much toned-down version, but she now realized that even literary people would not totally approve of what she wanted to do."

The dearth

of material about Bonner tested McAlexander's resourcefulness. He relied

on his own knowledge of Holly Springs, his connections there and the available

history. And he probed the lives of people she had known.

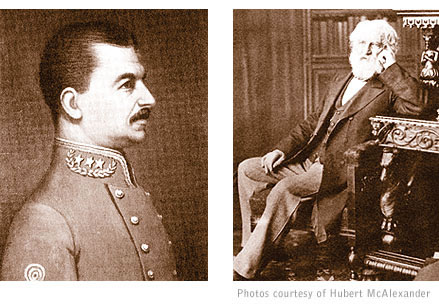

Bonner's

circle of friends included Memphis'most eligible bachelor, the retired

Confederate general Colton Greene (left), and the incomparable American

writer, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for whom Bonner worked as a secretary.

Those included her life-long friend and admirer, Scottish-born James Redpath - an ardent abolitionist, a New York Tribune editor, participant in the Underground Railroad, advocate of women╠s rights and labor reform, and biographer of John Brown. He established the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, which booked lecture tours for Frederick Douglass, Julia Ward Howe and Mark Twain, to name a few.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow also counted among her friends and admirers.

"He was infatuated with her. He loved younger women,"McAlexander said. "And she knew how to play him."

Longfellow was 67 when Bonner requested an audience with the renowned American poet. McAlexander writes of their first meeting:

“Indeed, as she stood in Longfellow's study, surrounded by the portraits of Sumner, Emerson, and Hawthorne, and examining the inkwell which had belonged to Coleridge, while this other great poet stood by her side, she knew that at last she had entered the great world. She intended to remain in it.”

And then there was the mysterious General Colton Greene. The former Confederate general was 44 and Memphis' most eligible bachelor when Bonner met him at the 1877 annual ball of the Mystic Society of the Memphi. She was 28.

McAlexander uncovered hints of the pair's relationship. No letters remain, if they ever existed, but Greene appears as a character in a number of Bonner's stories. Most telling was Greene's attention to the welfare of Bonner's daughter, Lilian. After Bonner's death, he purchased the Bonner family home and deeded it to Lilian, paid for her studies in Paris and bequeathed her nearly his entire, considerable estate.

Earlier Bonner biographies contained so many factual errors that McAlexander couldn't rely on their accounts. One listed daughter Lilian as a family friend. Others reported that Bonner never returned to Holly Springs following the 1878 yellow fever epidemic. Instead, McAlexander found that Bonner nursed her father and brother during the epidemic and returned months later to settle her father's estate. And when her health began to fail at age 34, she returned to Holly Springs to die.

"The yellow

fever epidemic is a big chapter in the history of my town. A lot of people

have written about it, including her," he said.

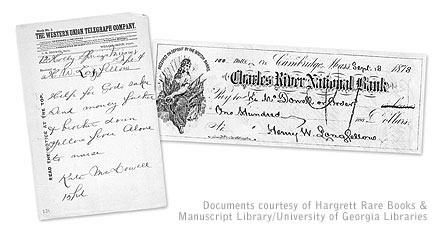

Known

to friends as Kate McDowell, Bonner received $100 from Henry Wadsworth

Longfellow following her impassioned plea for help during the 1878 yellow

fever epidemic that struck her hometown of Holly Springs, Miss., and took

the lives of her father and brother. (Documents courtesy of Hargrett Rare

Books & Manuscript Library/University of Georgia Libraries)

The epidemic reduced the town's population by one-fifth. McAlexander pieced together a riveting account of the epidemic based on an article Bonner had published in Harper's Weekly, her letters, a telegram from her to Longfellow and entries in Longfellow's journal.

Bonner was living in Boston at the time the epidemic began to spread north from New Orleans, and she became concerned about the safety of her young daughter in Mississippi. She hopped a train to Holly Springs. Within two days of her arrival, the town's former mayor became the epidemic's first casualty. She managed to send her daughter to safety but within the week, the disease had claimed the lives of her father and brother. Within two weeks, she was back in Boston.

In writing this section of the book, "I had to move her through fast just as it happened," McAlexander said, snapping his fingers to the rhythm of his words. "Move her through it, get the pace right, get her through it, get her back to Boston almost in shock."

Elderly people in Holly Springs provided other materials. "Attics were searched, boxes of rat-chewed papers produced, interviews freely granted and confidences shared," he wrote in the introduction to the paperback edition.

"The people in Holly Springs were great about sharing material," he said. "They're all dead now. I got that material at the last minute. I don't know where some of it is now."

McAlexander donated the materials he used to the UGA Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The collection includes photocopies of: Bonner's 1869 diary; letters to Longfellow, family and friends; census records; Colton Greene's will; and an annotated copy of Bonner's novel Like Unto Like that belonged to her friend Helen Craft Anderson.

The painstaking research on the Bonner book, which was published in 1981 and reprinted in paperback in 1999, was good preparation for McAlexander's biography of author Peter Taylor.

Intro

| A Mississippi lady |

Writing a writer's life

|

Patience and Fortitude

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()