Putting Organisms in Their Places

by Carole VanSickle

Intro/ Ecological Imbalance

| The Value of Little Green Things/ Toward Predicting Function

| Beetlemania/ Knowledge is Strength

![]()

Searching for Diamonds in the Rough

Intro

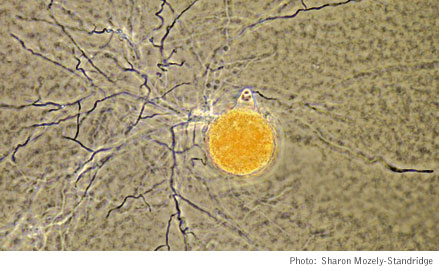

(Top) Euglena viridis, the first microscopic organism ever described, was first observed in 1674 by Anthony van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch scientist and tradesman who is considered the father of microbiology. Nearly 150 years later, German scientist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg classified the single-celled organism and gave it a scientific name. Illustration: Euglena viridis by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795-1876), Museum für Naturkunde, courtesy of Mark Farmer.

Scientists who systematically classify living things are themselves a threatened species. A major federal program aims to reverse this trend.

In 1997, when frogs at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., were contracting grotesque skin deformities and dying, a taxonomist — a scientist who focuses on the classification of living organisms — fingered the culprit.

Investigators in the case had been stymied until a technician noticed that a microorganism under the dead frogs’ skin resembled something he’d studied in college. So he snapped some pictures and sent them to two former professors: Mel Fuller, a retired botanist from the University of Georgia, and Joyce Longcore, a taxonomist at the University of Maine. The two identified the organism as an aquatic fungus called a chytrid.

“Longcore was one of the few people in the world who could have identified that organism,” said David Porter, professor of plant biology at UGA. But because the number of scientists being trained as taxonomists (also known as systematists) has been steadily declining, the next mystery like the chytrids could long remain unsolved.

“We’re losing experts in groups of organisms and in taxonomy in general,” said James Rodman, program director of the National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Biological Sciences, “and new ones aren’t being trained.”

That’s why the NSF introduced PEET (Partnerships for Enhancing Expertise in Taxonomy) grants in 1995 and has been awarding them to coalitions of taxonomists to investigate new or understudied organisms. These scientists catalog species, train the next generation of experts and share their findings via Internet databases. Of the 25 active grants across the country, UGA has three: a partnership between Porter, Longcore and University of Alabama researchers to analyze chytrids; a study of microscopic organisms called euglenoids by cellular biologist Mark Farmer; and a beetle study by entomologist Joe McHugh.

It took a taxonomist — a scientist who studies the classification of life forms — to identify the microscopic fungus, called a chytrid (above), that can wreak havoc on frog populations.

Ecological Imbalance

Although the chytrid stir at the National Zoo has died down, ailing frogs from Panama to Australia continue to be diagnosed with the problem. So the basic question for scientists is: Why now? After all, chytrids aren’t new to the amphibian scene — they date as far back as the Precambrian Age (some four billion years ago). So if chytrids have been dwelling in frog skin for eons, what is causing them to multiply now at such a dramatic and problematic rate?

“Chytrids can live almost anywhere there is water,” Porter said, “although they do not multiply so wildly under all conditions.” But when the environment is right, chytrids can wreak havoc.

These “die-offs” — massive and relatively sudden deaths in isolated frog populations — have serious ecological effects. Forests that once rang with the calls of scores of frog species now are nearly silent. For example, only “three very sick frogs” were found in one day on a recent stream survey in Central America, Longcore said.

“It’s important to recognize and understand even the minutest aspects of our environment,” she noted. “It will be a dull world someday if all we have are dandelions and a bunch of resistant insects because we did not understand the checks and balances within the biota of the earth, and why and how they influence each other.”

Intro/ Ecological Imbalance

| The Value of Little Green Things/ Toward Predicting Function

| Beetlemania/ Knowledge is Strength

For comments or for information please e-mail: rcomm@uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()