Listening to the Earth from Under

the Sea

by Carole VanSickle

Intro

| Where It All Began

| Seismic Forecasts?

| A Versatile Tool

![]()

Intro

Using specially designed equipment positioned on the sea floor some 2,200 meters down, University of Georgia physical oceanographer Daniela Di Iorio plans to listen in on the pulse of one the planet’s mid-ocean ridges. These geologically active, uplifted areas in the ocean floor, where magma from beneath the surface of the earth is forced between the boundaries of two oceanic plates, may provide insight to everything from evolution to earthquakes.

Next year, Di Iorio will begin monitoring a hydrothermal (hot-water) vent called Hulk on the Juan de Fuca Ridge west of Vancouver Island in Canada. She’ll use an acoustical system she helped develop as a graduate student and began refining with the help of a research services consulting company to monitor the “vitals” — such as temperature fluctuations and flow speed — of the scalding metallic plumes that steadily erupt into the ocean from deep within the earth.

In 2008, she and collaborator Peter Rona of Rutgers University plan to participate in the world’s largest cable-linked sea floor observatory project, the Northeast Pacific Time-Series Undersea Networked Experiments, also known as NEPTUNE. Using extensive networks of undersea instruments connected by fiber-optic and power cables to the observatory’s shore station, they’ll continually monitor the vitals of the vent field.

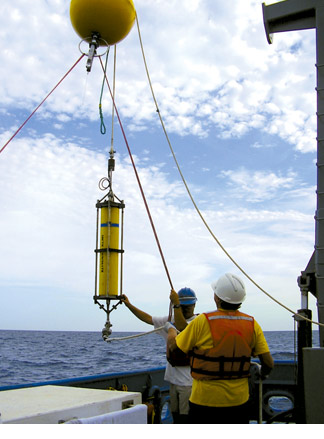

An acoustic transmitter and buoyancy float are being deployed to monitor a hydrothermal vent on the Juan de Fuca Ridge.

“In the past, the highly acidic and corrosive, 350-degree-Celsius water that spews out of hydrothermal vents prevented extended measurements because the instruments just couldn’t take the conditions for any long period,” Di Iorio said. “With my acoustical scintillation technique — which uses a separate transmitter and receiver placed on either side of the plume to measure sound-scattering by the turbulent properties of the buoyant plume – we can invert the signals to give water movements and temperature. We don’t put the instruments into the hydrothermal fluid at all.

“And there is no telling what the data could reveal about the inner workings of the oceanic plates and the movement of sea water through the sea floor,” she added, “because a hydrothermal vent is basically our nearest communication with the magma chambers underneath the earth’s crust.”

NEPTUNE will allow Di Iorio to constantly monitor and analyze her data, but until then her instrument will work as an autonomous, battery-operated and self-contained unit that’s able to store three to four months of data on a memory card.

“We’ll head out there, recover it, upload the data and change the batteries, then redeploy it,” she said.

Intro

| Where It All Began

| Seismic Forecasts?

| A Versatile Tool

For comments or for information please e-mail: rcomm@uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()