— K.M.T.C.

When you have a broken leg or the chicken pox, the problem is pretty apparent. But when your mind is broken or ill, the diagnosis can be harder to make.

However, a new technique in imaging that lets scientists peek inside the brain may help reveal when something is wrong or about to go wrong. Functional magnetic resonance imaging or fMRI not only gives researchers a snapshot of brain structure but also shows where brain activity is taking place as mental events are in progress.

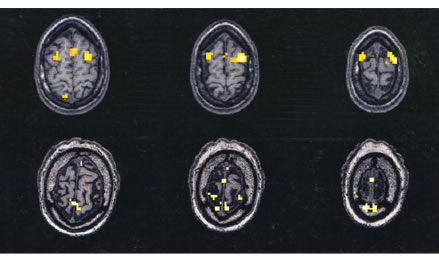

In one of Miller’s studies on aging, fMRI shows that the areas of the brain activated by memory (in yellow) change with age. A series of three slices of a 20 year old’s brain (three scans on top) are compared to a series of scans for an older adult (three scans on bottom). Courtesy of L. Stephen Miller.

“We can look at brain structure and learn a great deal,” said L. Stephen Miller, a psychology professor and co-director of the University of Georgia Human Neuroimaging Facility. “However, it doesn’t tell us anything about the activity of the brain — what’s going on when you’re trying to remember something or when you’re trying to do a particular task or when you’re having an hallucination or when you’re depressed.”

But using fMRI, the living brain can be studied as it is memorizing a list of words, experiencing an emotion or manipulating figures. To do this, a person lies face up on a movable table that slides into the bore of a 10-foot long, powerful magnet. Then standard MRI uses a combination of a strong magnetic field and radio waves rather than X-rays to produce a detailed picture of the brain. In addition, an fMRI scanner is adjusted to detect changes in the amount of oxygenated blood in regions of the brain activated during a mental task.

What scientists see in fMRI scans are pictures of the brain as if it had been sliced in thin sections, like a salami at the deli. Active areas representing the increases in oxygenated blood will “light up” on certain slices when that area has been stimulated during a mental task (see image above). This lets us “see” which areas of the brain are at work as we think.

At the University of Georgia, fMRI research is a collaborative effort that involves UGA, the Medical College of Georgia and HealthSouth, Inc. fMRI has become an important tool in a wide variety of brain research studies:

- In addition

to studies on schizophrenia, fMRI helps Miller’s research team

study how aging affects memory.

- Graduate

students under the direction of George Hynd, distinguished research

professor and associate dean in the UGA College of Education, use fMRI

to look at language deficits and reading disabilities in children.

- James Brown,

a UGA psychology professor, studies how visual information is processed

using fMRI.

- Psychology

graduate student Hope Denney asks subjects to tell lies as their brains

are scanned so she can uncover regions of the brain involved in deception

— part of a collaborative project with psychology professor Jennifer

Vendemia at the University of South Carolina.

- Nader Amir,

a UGA psychology professor, uses fMRI to find which areas of the brain

may be involved in anxiety disorders.

- Jennifer McDowell, a UGA psychology professor, studies eye-tracking deficits in schizophrenia with fMRI.

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()