terrorist attack

– Cham Dallas

Cham E. Dallas, a professor of toxicology in the College of Pharmacy, is director of both the UGA Interdisciplinary Toxicology Program and CLEARMADD, a CDC Specialty Center for Public Health Preparedness. For more than a decade he has been assessing nuclear contamination levels and environmental effects near the Chernobyl nuclear plant area, site of the world’s largest and most widespread radio-nuclide release. He also is a National Civilian Consultant for Weapons of Mass Destruction for the U.S. Air Force Surgeon General.

Americans now anticipate that Islamic and other terrorist organizations will use weapons of mass destruction (WMD) on U.S. soil. Federal, state and local governments are taking threats of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons very seriously and Congress has appropriated billions of dollars to increase our readiness to survive the magnitude of such attacks.

What form the attacks will take is the subject of speculation and confusion. Should we prepare for someone dispersing a shoulder bag of anthrax at Sanford Stadium? Will there be nerve gas in Atlanta’s MARTA transit system? Is it feasible to have a nuke from a stolen Russian warhead detonated in a van only one block from the state Capitol? Many people are wondering which threats are real, who the victims might be and how we would survive the aftermath.

The events of September 11 have sent a shudder through not just the American public, but also through the professionals that will be responding to mass casualty events. Our health care system is already stretched now in dealing with small numbers of patients —as few as 10 — from traumatic events. Doctors and emergency personnel just shake their heads at the prospect of dealing with thousands of victims at once, especially considering complications such as contamination with toxic agents.

When the Aum Shinrikyo doomsday cult released deadly sarin gas in the Tokyo subway, thousands of contaminated patients descended upon the local hospitals. In one hospital, six physicians and nurses were incapacitated by just one contaminated patient. In another, five out of the six available emergency doctors themselves had to be treated because of exposure to the patients, who were contaminated with the highly toxic nerve agent.

One can imagine the chaos that would ensue if the first line of emergency medical response was devastated within the first hours of the onset of a terrorist attack, leaving the community helpless to care for thousands of victims.

Research and training in response to large-scale disasters involving WMD components is not new to UGA. For more than a decade, we have had an active, innovative research program in the regions highly contaminated by the Chernobyl nuclear accident. We learned a great deal that is relevant to our current crisis from Chernobyl, the largest airborne radiation disaster in history (see UGA Research Reporter, Fall 1992 and Summer 1999). Of particular importance is the experience gained in observing the ineffective, indeed in many ways calamitous, emergency responses used by the Soviets in this disaster. For instance, the Russians did not distribute protective iodine tablets to the people in the exposed areas until more than three days after the accident. Thousands of radiation-induced thyroid cancers occurred in exposed children. This medical tragedy was nearly 100-percent preventable, had the pharmacy community been sufficiently trained and prepared to issue the iodine tablets to children within 12 hours of exposure.

Therefore, one of the most critical steps in preparing for large-scale WMD attacks is the research and education needed to prepare key health professionals to handle the mass casualties expected. In addition to traditionally recognized first responders — police and firefighters — medical professionals are critical to effective responses to a large-scale WMD casualty cascade. New training is needed, of course, for physicians and nurses. But another key group in the WMD response is pharmacists, who must be trained to dispense the large quantities of antidotes, antibiotics and other medicines needed for mass distribution, especially from the National Pharmaceutical Stockpile.

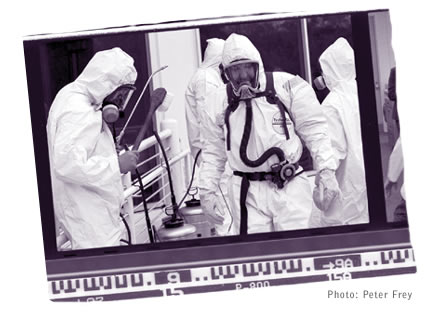

Above: Cham Dallas directs a mock terrorist attack on the University of Georgia campus. The simulation was used to determine how medical and emergency personnel would respond to a bioterrorism attack involving mass casualties.

Veterinarians and agricultural extension agents would be summoned in the event of agroterrorism against crops, livestock and other animals, as evidenced by naturally occurring international outbreaks of hoof-and-mouth disease in recent years. Other healthcare responders include environmental health experts, toxicologists and geographic information specialists.

In a WMD crisis, all these healthcare responders would operate under the incident command structure established by the state to coordinate local, state and federal resources.

The University of Georgia is uniquely positioned to meet this need through the Center for Leadership in Education and Applied Research in Mass Destruction Defense (CLEARMADD). This national center is one of the CDC’s eight Specialty Centers for Public Health Preparedness, which form a national network that develops WMD emergency procedures. CLEARMADD focuses on procedures for pharmacy, veterinary medicine, agroterrorism and emergency medicine (in collaboration with the Medical College of Georgia).

Procedures developed for training healthcare responders will be validated for establishing national standards of training for large-scale WMD response. Media products are also being developed for distribution statewide and nationwide for WMD professional training and public education. In addition, CLEARMADD also provides for UGA research on biologically based detection, patient biomonitoring and pharmaceutical treatment.

Many Americans now believe it is not a matter of if but when some form of devastation from WMD will occur in this country. Higher education has a major role to fulfill in preparing our healthcare community to alleviate the impact of these attacks.

For more information, contact cdallas@mail.rx.uga.edu

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()