by Whit Gibbons and Kimberly Andrews

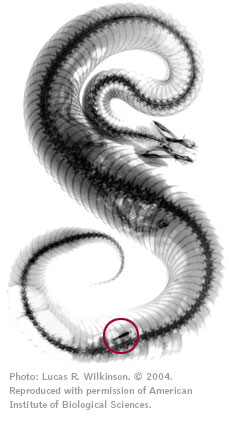

Tony Mills caught the eastern kingsnake to tag it and study the snake’s behavior following release. But a routine scan with a special handheld reader showed that the big snake already had an electronic tag inside its body — one belonging to a black swamp snake.

Mills, an environmental educator at the Savannah River Ecology Lab (SREL), was using a simple technology called PIT tagging when he unexpectedly documented, for the first time, that eastern kingsnakes eat black swamp snakes.

Ecologists and wildlife biologists depend on “mark-recapture” techniques to study animals in nature. An animal is marked with a personal identification number, released and recaptured weeks, months or years later. Information about that individual can help uncover how fast the animal grows, where it lives and how long it survives in the wild, for example. For such purposes, PIT tags are an advancement in the state of the art. They are more dependable than traditional external markings, such as ear tags, leg bands or fur dyeing, which can be lost, become illegible or even alter social interactions.

PIT tags — short for passive integrated transponder devices — are microchips embedded in glass casings. These tiny coded markers — the size of a grain of rice — are injected under an animal’s skin, into muscle or a body cavity, and can transmit a number that identifies the individual as reliably as a fingerprint or bar code.

These tags have been used to study animals as diverse as fish, bats, sea otters, desert tortoises, penguins and crayfish. They help trace livestock suspected of harboring diseases (such as mad cow or hoof-and-mouth) to their original herds, and confirm the identity of zoo animals, pets or protected species illegally removed from the wild. By PIT tagging rat snakes, for example, SREL scientist Bobby Kennamer discovered that they returned to the same wood-duck box year after year for a predictable meal; Kennamer suggested that moving the boxes might improve wood-duck reproduction.

PIT tags have some limitations at present, including high purchase cost and low detection distance. Nevertheless, they can help advance animal physiology and conservation biology, as well as improve scientists’ understanding of social interactions among individuals in a population. They can even show that one snake dined on another.

For more information, contact J. Whitfield Gibbons at gibbons@srel.edu.

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()