The Media are the Message

by Carole VanSickle

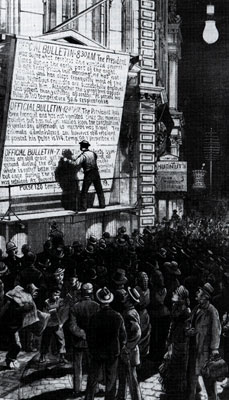

Posting Garfield's medical bulletins under the electric lamps on Broadway. From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, 3 Sept., 1881, p. 9. Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

James Garfield’s short presidential term was ended in 1881 by a madman’s revolver, but his extended demise, which lasted almost three months while doctors prodded his infected wound in search of the deadly bullet, marked the beginning of modern news-media dynamics, said Richard Menke, an English professor at the University of Georgia. “The assassination coverage forged relationships between technology, literature and the media.”

Continuing series of media episodes now permeate everything from pop culture to the war on terrorism. “Technology — whether the telegraph or the Internet — decouples language from reality and the focus shifts from content to the process of dissemination,” Menke said.

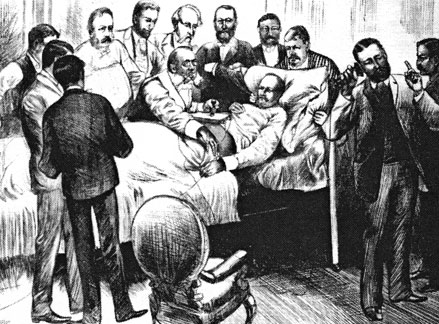

As the intense coverage of Garfield’s status expanded to include ruminations about the site of the missing bullet, Alexander Graham Bell tried to bring his new telephone technology to bear. He hastened to the president’s bedside with the earliest metal detector on record — a result of Bell’s collaboration with Simon Newcomb, who had published theories on electromagnetic metal detection in a national newspaper. Their efforts, though unsuccessful for the president (in retrospect, possibly because of the then-recently invented metal-coil-spring mattress on which he lay) nevertheless showed that “the day when science shall have interwoven human thought and interest [into] universal kinship” was near, said Scientific American.

Many historians believe that Garfield could have survived had he not been so zealously attended.

“Like Sept. 11, Garfield’s assassination was — at the time — an unprecedented tragedy eliciting an unprecedented response,” Menke said. Simultaneous and ubiquitous emotions among millions of people, such as concern for a dying president or grief following the Sept. 11 attacks, create unity that may itself become the target of media coverage. “Yet historical perspective indicates we should be wary of experiencing media effects on an intimate psychological front. As a nation, we may feel that we are suffering en masse, but the overwhelming experience of involvement often terminates in amnesia as coverage overshadows the original event.”

Walt Whitman’s poem, “The Sobbing of the Bells,” published after Garfield’s death, illustrates the implications of our weak cultural memory, Menke said. “The poem doesn’t even mention the president, because the poet assumed that the news was so widely understood that he didn’t need to specify his subject. But now that Garfield and his assassination have largely been forgotten, the poem’s reference is obscured.”

For more information contact Richard Menke at rmenke@uga.edu.

For comments or for information please e-mail: rcomm@uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()