From Farm to Fork

![]()

E. Coli Fears May Spur

More Oversight

Consumers’ love affair with pre-washed, bagged fresh produce, a $2.8 billion-a-year industry, chilled last fall following a nationwide outbreak of food-borne illness resulting from contaminated bagged spinach.

Although it is clear that the dangerous E. coli O157:H7 pathogen was the cause of the outbreak, more than six months later, it has not been determined precisely how the contaminant was introduced.

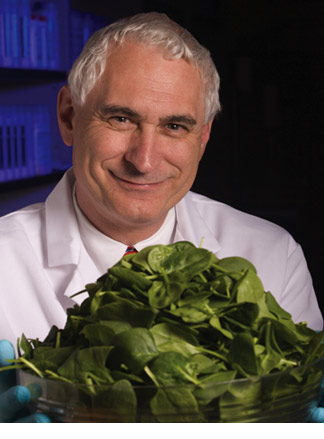

Will consumers’ desire for healthful veggies override their concern for safety? Research Magazine talked with food scientist Michael Doyle, director of UGA’s Center for Food Safety, about the long-term outlook for safe produce.

Let’s talk about the good news first. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates tens of millions of illnesses, 325,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths result from food-borne illness each year in the U.S., yet this represents a major improvement. What big steps contributed to that reduction?

Doyle: We do have good news. In the last five years the incidence of food-borne illness has gone down. Information from the CDC shows that illness from most major pathogens is down: Salmonella is down by about 10 percent, and E. coli O157:H7, campylobacter and listeria are all down by about 30 percent. So we’re seeing improvement. The bad news is that we’re still seeing millions of cases each year.

On the plus side, the meat industry has adopted the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point system (HACCP), a science- based system of controls applied from farm to processing plant, to cut the incidence of E. coli and Salmonella contamination in half. But the produce industry still has a long way to go.

Why are we seeing this increase in produce-related illness?

Doyle: We’re eating more produce than two decades ago—consumption has about doubled in that time. We also have better surveillance, which means we detect more illness. With new notification systems, the CDC can identify produce-related outbreaks much quicker than in the past. We’re also importing a lot more produce—more than 35 percent of fresh produce consumed in the U.S. is imported—and that will increase. And not all countries we import from have as good sanitation we do in this country—which is not to say that we don’t have problems in the U.S. Since fresh produce is usually eaten raw it is not given a heat treatment, like most meat we eat, to kill harmful microbes.

How much can advances in food science and technologies contribute to keeping produce safe?

Doyle: Food scientists are very involved in developing interventions in different segments of the industry. In the meat and poultry industries, for example, we have steam pasteurizing, which kills bacteria on the surface of carcasses, chemical sprays and hot water sprays—all of which greatly reduce the risk of pathogens.

The same has to be done for fresh produce. But this is a harder nut to crack, because some types of produce don’t tolerate these kinds of intervention. We also know that chlorine treatments used in wash water are not effective in eliminating harmful microbes on produce.

Americans demand cheap, but safe, food. Is that unrealistic?

Doyle: If you go overseas you’ll see that Europeans pay as much as four times more than what we pay for food. They take a lot of precautions in Sweden, for example, to reduce contamination, but it comes at great cost. We have a bigger challenge here in the U.S. We can’t adopt those same systems–they’re on a much smaller scale there. But we have learned of some cost-effective ways to reduce Salmonella and E. coli contamination, for example, on the hides of animals.

What’s the likelihood we’ll see changes by the produce industry?

Doyle: Some companies are very serious about change. Others are going to wait and see if the consumer will continue to buy their products before investing in major changes.

Are you saying that consumers need to speak with their pocketbooks?

Doyle: That’s what it will take in the long run. Some retailers are also very concerned and are actively communicating their concerns to the produce industry.

Putting food on the table involves a lot of places, people and processes that can cause contamination. How do food scientists know where to focus?

Doyle: It’s a question of where we can get the biggest bang for the buck—of analyzing where the risk lies and applying interventions where they have the most impact on reducing contamination. We need to look at the entire system, from farm to fork. We’ve done that for E. coli O157. There, a risk assessment identified specific points in the food chain that were the greatest risk, and we applied interventions at those specific points to get the greatest benefit. We know that there are many points for contamination to occur in the produce industry, from production to the home. There is not a simple solution to making fresh produce safe, but it will require a multitude of approaches.

So it sounds like the future of food safety is, in large measure, up to consumers.

Doyle: Consumers can put pressure on industry to do more. But they also have at their disposal interventions that can be used in the home. Take, for example, fresh lettuce. Handling it properly means removing the outer leaves, washing your hands afterwards, and then washing the inside leaves. But with bagged cut lettuce, there’s no way you can completely wash away microbial contamination. It’s the same with meat and poultry. Industry has done a lot to reduce bacteria, but it can still be contaminated, and consumers still need to handle and cook it properly.

For more information contact Mike Doyle at mdoyle@uga.edu.

For comments or for information please e-mail: rcomm@uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()