The Bug That Made Milwaukee Famous

By Renee Twombly

In Search of Crypto's Achilles Heel

When Dan Colley moved from Vanderbilt University to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta to be Chief of the Parasitic Diseases Branch, he thought he’d be deskbound. But within months he found himself in Milwaukee, on the shores of Lake Michigan, wondering how so many individuals could have gotten ill at the same time. “Four hundred thousand cases of diarrhea was a bad way to start a job,” he said.

It all began on April 5, 1993, with unusual levels of absenteeism at local workplaces and schools. By April 7, as the number of sick people reached epidemic proportions, a “first alert” team of state public health experts told the 600,000-plus residents of Milwaukee that they would have to boil their drinking water. This advice was prompted by the cloudy water from the city’s south-side drinking water filter facility and reports from several alert physicians who examined stool samples from patients and found a little “bug” called Cryptosporidium.

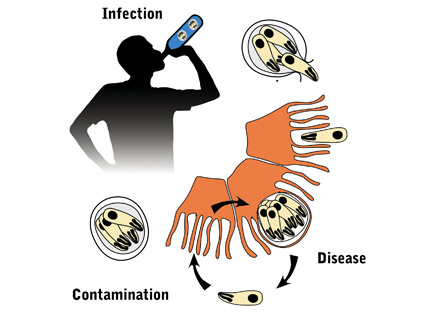

Cryptosporidium can hitch a ride on food-or in water-causing diarrhea and even death in vulnerable individuals.

Pin-Pointing The Source

“Outbreak investigations are what the CDC does best,” said Colley—who soon found himself directing what amounted to a squad of detectives, including both epidemiologists and laboratory personnel. From household surveys, he and his team estimated that some 403,000 people across the city were sick, but that number didn’t help pinpoint the location of the outbreak because people constantly move around the city. Investigators looked at residents of 16 nursing homes, on both the north and south sides, because these folks don’t often leave their abodes. They observed that 51 percent of nursing-home residents on the south side got sick while none did on the north side. Also, south-side residents whose homes drew on well water were just fine.

“These results told us very clearly that the source was drinking water processed at the south plant,” Colley said. He also noted that some travelers moving through the Milwaukee airport between planes also became ill after drinking from a water fountain. The city’s airport is on the south side.

Investigators started seeking the culprit by looking at local slaughterhouses, run-off from nearby dairy farms and the possibility that the outbreak came from human sewage overflow. It turned out that the intake for the drinking-water treatment plant was just too close to the outflow pipe from a sewage-treatment plant. This unfortunate configuration had apparently caused a total of 4,400 hospitalizations and 12 fatalities.

The CDC and its partners produced a comprehensive handbook on human infection by Cryptosporidium, noting that it is very hard to kill. “Crypto laughs at the concentrations of chlorine used in treatment plants,” Colley noted. The main solutions are expensive filtration systems or a protected water source. So Milwaukee spent millions of dollars to add new and better filtration and change the plants’ configurations. Researchers at the CDC and Emory University estimate the cost of the outbreak at $96 million in medical expenses and lost productivity.

Vindication The Farmers

Meanwhile, work on Cryptosporidium continued unabated at the CDC, and Colley, who holds a Ph.D. in immunology and microbiology, was made director of the Division of Parasitic Diseases later that year. “Cryptosporidium was still on my watch, and, in fact, it now had an even higher profile,” he said.

CDC scientists and academic researchers soon found out that there are many Cryptosporidium subspecies, including “a human isolate”—a form that infects just people. In fact, scientists now say that much of the U.S. population has antibodies to the parasite, meaning they have been exposed to it at some point.

“It was in 1996 that we finally discovered that cows [the usual source] weren’t involved in the Milwaukee outbreak,” Colley said. “The farmers were finally vindicated.” Colley left the CDC in late 2001 to become director of UGA’s Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases, which includes a focused research program in Cryptosporidium. “The bug is still with me,” he quipped. “Quite possibly literally.”

For comments or for information please e-mail: rcomm@uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()