Terrapins in Trouble

Diamondbacks in coastal marshes from Massachusetts to the Texas-Mexico border face threats, largely human-made, to their survival. But individuals and state governments are starting to take action.

In a ritual that has played out every spring for tens of thousands of years, female diamondback terrapins—colorful and beautifully patterned marsh-dwelling turtles—crawl out of tidal creeks and head for higher ground to lay their eggs. On Georgia’s Jekyll Island, and in countless other marshes along the Atlantic coast and Gulf of Mexico, that often means the terrapins must cross a road to reach their nesting grounds. For those thousands a year unlucky enough to meet up with vehicles during the crossing, their remains dot the highways in bloody humps of crushed shell and meat.

In a ritual that has played out every spring for tens of thousands of years, female diamondback terrapins—colorful and beautifully patterned marsh-dwelling turtles—crawl out of tidal creeks and head for higher ground to lay their eggs. On Georgia’s Jekyll Island, and in countless other marshes along the Atlantic coast and Gulf of Mexico, that often means the terrapins must cross a road to reach their nesting grounds. For those thousands a year unlucky enough to meet up with vehicles during the crossing, their remains dot the highways in bloody humps of crushed shell and meat.

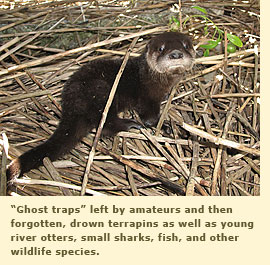

Back in the marsh, the much smaller males and juveniles face another indiscriminate predator: crab traps, where many more, drawn by the smell of rotting meat used as bait, crawl in and, unable to escape, drown. For UGA’s Andrew Grosse, who has been surveying Georgia’s terrapin population for the past two years, viewing the contents of one of these “ghost traps,” left by amateurs and then forgotten—is a gut-wrenching experience.

“It’s one thing to read about turtles drowning in crab traps,” he said. “But to see 94 dead in just one trap, clustered near the top where they were straining to get air, is gruesome.”

Grosse, a graduate student in wildlife ecology, is assessing the relative effects of busy roads and crabbing on Georgia’s terrapin population. He’s also trying to determine whether sex ratios are skewed by the fact that female terrapins predominantly die on roads while more males drown in crab traps. Funded by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, the research is the first to investigate the status of the state’s diamondback terrapin population.

The two main threats

Georgia’s busy coastal roads take a significant toll on terrapins, especially females, which account for 98 percent of the road-killed terrapins in Grosse’s survey. Officials at the Jekyll Island Sea Turtle Center, which rehabilitates injured terrapins in addition to sea turtles of all kinds, said that more than 300 terrapins were killed by vehicles in 2007 on the Jekyll Island causeway alone.

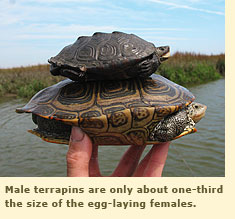

The data show as well that commercial and recreational crab traps also kill many terrapins, 80 percent of them males. Being about one-third the size of females, males fit more easily through the narrow openings in crab traps. “Terrapins can only stay submerged for a few minutes before they drown, especially when stressed,” Grosse explained.

The data show as well that commercial and recreational crab traps also kill many terrapins, 80 percent of them males. Being about one-third the size of females, males fit more easily through the narrow openings in crab traps. “Terrapins can only stay submerged for a few minutes before they drown, especially when stressed,” Grosse explained.

So far, the study has not shown an effect on terrapin sex ratios because of the losses from roads and crabbing, as did an earlier study in South Carolina. But researchers say that without further protection in Georgia, its population of diamondback terrapins is likely to decline, as have those in other states.

“We still have an opportunity to preserve these critical habitats in Georgia,” said John Maerz, a herpetologist in UGA’s Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources and Grosse’s thesis advisor. “But as the last 100 miles or so of the coast develop, there’s serious concern over the terrapins’ ability to persist.”

Collateral damage

During this country’s history, terrapins have fed the desperately poor and the well-to-do alike. They sustained slaves on tidewater plantations as well as poor families living in remote coastal communities. The soldiers of the Continental Army fed on terrapins as they moved through marshes. And from the late 1800s until the Great Depression, terrapin soup was a popular item in highbrow East Coast restaurants, where affluent diners slurped the sherry-laced soup from special bowls made just for the purpose.

As a result, the diamondback was hunted nearly to extinction in the mid-nineteenth century. Demand for terrapin meat has subsided considerably since then, despite a burgeoning U.S. and world market driven by Asians. The reptile today faces more serious threats, however. Aside from the coastal development that brings with it more roads, traffic, pollution, boats, and marsh-side homes, together with commercial and recreational crabbing, there is also an overabundance of natural predators, such as raccoons, that dig up and eat terrapin eggs.

Perhaps most heartbreaking is that the toll on terrapins is largely incidental. Few crabbers, drivers, or coastal developers set out to kill the turtles; indeed, few are even aware of them, much less their struggle to survive.

“They live on the other side of the island from the beach, so most people never see them,” explains Whit Gibbons, UGA professor of ecology, who has chronicled the decline of the diamondback terrapins in the marshes of South Carolina for 30 years. “Commercial crabbers hate to find dead turtles in their traps,” he said. “But they check their traps fairly often. It’s the recreational crabbers—who come down a couple of times a year, throw a trap off the end of a dock, and leave it in the water—who kill hundreds of terrapins, and a lot of other animals as well. We’ve also found blue crabs, small sharks—even dead otters—in these ghost traps. They’re devastating to wildlife.”

“They live on the other side of the island from the beach, so most people never see them,” explains Whit Gibbons, UGA professor of ecology, who has chronicled the decline of the diamondback terrapins in the marshes of South Carolina for 30 years. “Commercial crabbers hate to find dead turtles in their traps,” he said. “But they check their traps fairly often. It’s the recreational crabbers—who come down a couple of times a year, throw a trap off the end of a dock, and leave it in the water—who kill hundreds of terrapins, and a lot of other animals as well. We’ve also found blue crabs, small sharks—even dead otters—in these ghost traps. They’re devastating to wildlife.”

According to the Department of Natural Resources, Georgia has 146 licensed commercial blue crabbers who set out some 17,850 crab traps—an average of 122 per crabber. Some have agreed to try bycatch-reduction devices (BRDs), rectangular wire attachments that allow crabs to enter a trap but exclude turtles, unless they are quite small. While excluder devices are required equipment in Northeastern states, their use is still voluntary in Georgia, and attempts to get crabbers to use them, even at the state’s expense, have so far been unsuccessful.

Considering the consequences

Today diamondback terrapins are declining drastically throughout their range, which extends from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, south around the Florida coastline to the Texas-Mexico border. Despite their extensive distribution, they survive in isolated pockets among fragmented habitats; thus their total area of occupancy, and numbers, are relatively small. This, together with the fact that terrapins mature slowly and don’t reproduce until they’re five to eight years old, makes them especially vulnerable to extinction.

Terrapins have no federal protection, but the states are beginning to take action, mostly in response to research and education efforts. In Maryland, where the diamondback terrapin is the official state reptile—and the mascot of the University of Maryland, the state’s flagship university—a bill passed in 2007 makes it illegal to take or possess a terrapin for commercial purposes. South Carolina also passed legislation in 2007 that bans the possession of more than two diamondback terrapins at a time.

“The laws are part of an awareness campaign,” said Gibbons. “Terrapins are showing up in seafood markets in New York and San Francisco, which is just inappropriate these days. The shipment alone is inhumane.”

In other states throughout their range, the level of protection for terrapins varies widely. In Rhode Island, they are listed as “endangered”; in Massachusetts, they are “threatened.” New Jersey restricts the harvest of terrapins to five months a year—November through March—and requires the use of turtle-exclusion devices on all crab pots. In North Carolina, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, Virginia—and Georgia—the terrapin is simply a “species of concern.”

Wherever it persists, the terrapin has devoted fans—not only researchers but also teachers, students, and volunteers. Some patrol causeways and coastal roads, collecting still-viable eggs from dead female terrapins; others give presentations at schools, churches, and civic clubs about the growing human-induced threats to terrapins. Still others help biologists with the muddy task of temporarily capturing, measuring, and counting terrapins to add to the scant information that researchers already have about this struggling species.

Despite all he knows about the diamondback’s troubled past and improbable future, Gibbons remains optimistic. “I know that attitudes can change when people become aware of the terrapins’ plight,” he said. “And there are a lot of good efforts out there to let them know what’s happening and how they can help.”

One good way to help is to oblige developers, whether private or public, to widen their concepts of environmental impact. “The Departments of Transportation are very concerned about the loss of wildlife on highways nationwide,” Gibbons observed. “And as I’ve said before and will say again: We should never, ever, build another highway without first considering the consequences to our wildlife.”

(Helen Fosgate is editor of ugaresearch).

For more information visit the Terrapin Project web site: http://jcmaerz.myweb.uga.edu/lab/Terrapins/index.htm

|