Teaming Up Against Cancer

The UGA Cancer Center is fighting the disease, and addressing its implications, through a diversity of targets, tactics, and protagonists.

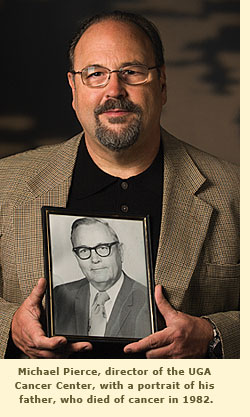

On a conference-room wall near Mike Pierce’s office are two prominent photographs, hanging side by side. On the left is a man in his 40s, wearing a dapper suit and a beaming smile. On the right is a younger man. He sports red and white flowers in the lapel of his suit, his head is shaved, and he’s smiling too.

One man survived his cancer, the other did not. Both photos are reminders that the disease can strike anyone at anytime, and Pierce, who was recently named the George E. and Sarah F. Peters Mudter Professor in Cancer Research, says they are tremendous sources of inspiration: “So we go into the lab and try as hard as we can to make discoveries that will have an impact.”

The UGA Cancer Center is just four years old. But already it includes more than 40 teams of scientists and other professionals from across campus who are pursuing research they believe has potential to significantly improve cancer prevention and treatment. The center is exploring new diagnostic tests and new treatments, for example, and working to improve cancer-prevention messages and the quality of life of patients and survivors.

The UGA Cancer Center is just four years old. But already it includes more than 40 teams of scientists and other professionals from across campus who are pursuing research they believe has potential to significantly improve cancer prevention and treatment. The center is exploring new diagnostic tests and new treatments, for example, and working to improve cancer-prevention messages and the quality of life of patients and survivors.

“We have a diverse group of researchers,” says Pierce, “because there are so many different ways to affect the multiple problems of cancer.”

Redefining Early Detection

The picture on the left in Pierce’s conference room is of Howard Young, a UGA alumnus and pancreatic-cancer survivor; he is among the fortunate five percent still alive five years after being diagnosed with the disease. A certificate of thanks sits under the photo, recognizing Young’s critical role in helping Pierce and his colleagues search for a way to find the disease early, when the prognosis for survival is best.

Lance Wells, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology and Georgia Cancer Coalition (GCC) Distinguished Cancer Scientist, (see related article) explains that when cells become cancerous—but long before any changes can be detected with X-rays and MRIs—the proteins and sugars that adorn them undergo distinct changes. The UGA scientists had the expertise and the equipment to identify such changes, but they lacked samples from patients. Young introduced them to doctors at the clinic where he was treated—the Translational Genomics Research Institute in Phoenix, Arizona—and a collaboration was born.

With $2.1 million in funding from the National Cancer Institute and support from the Georgia Research Alliance, the researchers are examining samples of pancreatic ductal fluid to search for telltale signs of malignancy. The ultimate goal is to create a blood test for pancreatic cancer, and the researchers hope to have such a diagnostic test in clinical trials by the end of their five-year study period.

“If there is a biomarker for pancreatic cancer, I’m confident that we can find it,” says Wells, who is studying the samples with Pierce and their colleagues Mike Tiemeyer, Ron Orlando, and Kelley Moremen.

Tomorrow’s Treatments

Understanding the changes that cells go through when they become cancerous can lead to new treatments as well.

At the UGA College of Pharmacy, biochemist Shelley Hooks is examining a pathway that drives the growth and metastasis (the spread to other parts of the body) of ovarian cancer cells. As a cell becomes malignant, it starts producing a growth signal called LPA, which helps to promote malignancy elsewhere. But Hooks has discovered that a class of proteins can turn off the LPA signal, and she aims to use it as the basis for drugs that stop ovarian cancer’s progression.

Another cellular signal gone awry involves a molecule known as RAS. In normal quantities, it helps control cell growth. Too much, however, leads to uncontrolled cell growth. Walter Schmidt, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology, is looking for ways to shut down—or at least substantially diminish—an enzyme that is critical to the excess formation of RAS. “By blocking this step, you block the ability of these cells to communicate, and hence the development of cancer,” says Schmidt, a GCC Distinguished Cancer Scientist.

Meanwhile, Franklin Professor of Chemistry Geert-Jan Boons has created a vaccine that—in mice—trains the immune system to recognize and attack cells bearing carbohydrates that are unique to tumors. Other researchers have created similar experimental vaccines by linking tumor-specific carbohydrates to naturally derived and purified proteins, but in these cases the immune system tends to attack the proteins, which it perceives as foreign, rather than the carbohydrate. Boons’ vaccine, on the other hand, uses a protein that is fully synthetic and is not perceived by the body as foreign. The result is that the full force of the immune attack is directed at the cancer cell bearing the target carbohydrate.

“Our immune responses are over 100 times more potent than traditional vaccines,” said Boons. He hopes to begin clinical trials in humans within a year.

Vladimir Popik, associate professor of chemistry and GCC Distinguished Cancer Scholar, is working to substantially reduce the toxic side effects of chemotherapy drugs. He has modified potent tumor-killing compounds so that they are active only for a short period of time—when exposed to a light of a specific wavelength—and he is now working to ensure that these compounds bind to the tumor’s DNA.

Vladimir Popik, associate professor of chemistry and GCC Distinguished Cancer Scholar, is working to substantially reduce the toxic side effects of chemotherapy drugs. He has modified potent tumor-killing compounds so that they are active only for a short period of time—when exposed to a light of a specific wavelength—and he is now working to ensure that these compounds bind to the tumor’s DNA.

“We have a warhead, and now we need a targeting system that would actively bind to DNA,” Popik says. “Then we could use a laser to trigger the ‘explosion.’”

Supporting Mind and Spirit

Looking beyond the cells and tissues, some researchers at the UGA Cancer Center are studying how the disease affects the daily lives of individual survivors, at both ends of the age spectrum, and of their loved ones. Claire Robb of the College of Public Health is focusing on older cancer patients while Stephanie Burwell of the College of Family and Consumer Sciences is addressing younger patients. In contrast to most quality of life research, Burwell’s work also addresses the needs of loved ones.

“Because most cancer research focuses on patients, their partners and family members are often left out,” she says. “I want to develop and test psychosocial interventions to help women living with breast cancer and their partners and families. There are very few interventions like this right now.”

Jeff Springston of the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication works to help people benefit from regular cancer screenings. Rather than relying on pamphlets and other traditional media, which typically take a one-size-fits-all approach to health communication, he is using new media technologies such as interactive kiosks and DVDs to target messages to specific populations.

Jeff Springston of the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication works to help people benefit from regular cancer screenings. Rather than relying on pamphlets and other traditional media, which typically take a one-size-fits-all approach to health communication, he is using new media technologies such as interactive kiosks and DVDs to target messages to specific populations.

Springston, a core-director of UGA’s Southern Center for Communication, Health, and Poverty, is himself a prostate-cancer survivor. “Had I not been sensitized to the importance of cancer screenings through my work, I’m not sure I would’ve found my cancer as early as I did,” says Springston. “This is an area where communication can make a real difference in life-or-death decisions.”

Long-Term Commitments

Despite their affiliation and commitment, many of the professionals at the UGA Cancer Center don’t think of themselves exclusively as cancer researchers. They are simply applying their knowledge and skills to investigating cancer, and many point out that their work also has applications to other diseases, such as diabetes and Alzheimer’s.

Yet while researchers at the Cancer Center pursue their work, often in collaboration with colleagues at clinics, medical centers, and pharmaceutical companies across the country, all of them understand—whether they call themselves cancer researchers or not—the importance of their work. Alongside the photo of Young, the pancreatic cancer survivor whose portrait hangs in the conference room, is a photo of Avinash Sujan, a promising post-doc, who died of a brain tumor. Though determined, the researchers know that it will likely take years before their findings translate into front-line treatments.

This is the way it must be, as tomorrow’s treatments and other advances will necessarily be rooted in today’s basic research, which is usually a trial-and-error, painstaking, and time-consuming process. “To combat cancer, we need new approaches and new understandings,” says Boons, “and that is what basic research can offer.”

(Sam Fahmy is a UGA science writer and frequent contributor to ugaresearch).

To learn more about the UGA Cancer Center, visit: www.uga.edu/cancercenter

The University of Georgia’s McPhaul Family Therapy Clinic offers counseling services on a sliding-fee scale for patients, partners and families dealing with cancer.

For more information, call (706) 542-4486 or visit www.fcs.uga.edu/cfd/mft/clinic.html

|