Georgia's Fragile Coast:

Will Building Green Pay Off?

Developers begin to realize, and UGA researchers confirm, that business savvy and environmental good sense are often in sync.

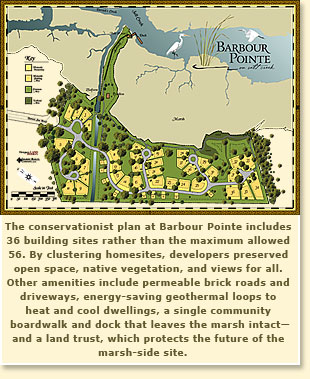

The roads at Barbour Pointe—a marsh-side Savannah development of 36 homesites—are literally paved with good intentions, brick pavers laid down in a pattern that allows water to seep through and move into the soil in a benign and natural way. With similar intent, Barbour Pointe developers Gregg Bayard and Curry Wadsworth have clustered homesites to create an extensive common area, preserved as much natural vegetation as possible, installed geothermal loops for heating and cooling, created low-impact access for canoes and kayaks into an adjacent marsh creek, and provided other environment-friendly features as well.

The project is moving along. Indeed, as Wadsworth recently noted while watching a landscaping crew arrange flats of grass along one of the development’s permeable roadways, “I love it when the sod goes down. It means you’re almost done.” But now comes the hardest part—waiting to see how the Savannah housing market reacts to the sustainable features in which he and Bayard have invested so heavily. Will potential buyers reward them for their green efforts?

The project is moving along. Indeed, as Wadsworth recently noted while watching a landscaping crew arrange flats of grass along one of the development’s permeable roadways, “I love it when the sod goes down. It means you’re almost done.” But now comes the hardest part—waiting to see how the Savannah housing market reacts to the sustainable features in which he and Bayard have invested so heavily. Will potential buyers reward them for their green efforts?

As if anticipating this question, two University of Georgia researchers, Warren P. Kriesel and Jeffrey D. Mullen of the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, just completed a study titled “Are There Incentives for Growing Green? Evidence from the Coastal Marshlands of Georgia.”

Funded by Georgia Sea Grant, Kriesel and Mullen’s investigation found that for homes within about a third of a mile of the marsh, every one percent of common space relative to the entire development boosts the price of each home by $3,300. Thus with 55 percent of Barbour Pointe’s buildable land in commons, each home’s sales price potentially supports a premium of more than $180,000. “The story,” said Kriesel, “is that people can’t seem to get enough of open space.”

This finding not only bodes well for the developers of Barbour Pointe, it also is good news for those concerned that booming coastal development will harm sensitive marsh environments. Once developers learn that it pays to preserve land adjacent to ecologically precious areas, the market might begin to do what regulation has been slow to accomplish. And the developers of Barbour Pointe went beyond just setting aside common space: they put it in a land trust. So in addition to being able to charge more for their homesites, they will reap a significant tax deduction for the charitable donation of prime marsh-side real estate.

Could this be a new model for coastal real-estate development—higher profits for developers who, acting in their own interest, reduce building density in critical environments? Researchers seem to think so. A collaborative study by scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Coastal Division, and the Georgia Conservancy is now posted on www.csc.noaa.gov/alterantives. The study, “Alternatives for Coastal Development: One Site, Three Senarios,” evaluates the economic, environmental, and social impacts of three design scenarios—conventional, new urban, and conservationist—for the development of a hypothetical piece of coastal real estate. Besides receiving poor environmental and social marks, the conventional design was clearly the least profitable for the developer, even though it generated more homes and more gross revenue.

UGA’s Kriesel acknowledges that his and Mullen’s work was inspired by the study. “We looked on it as a good start,” he said, “but we wanted to expand the information base with actual figures from Chatham County.” And the real data gave them similar results.

“From the beginning,” says Barbour Pointe’s Bayard, “we were looking to maximize net over gross. If we had done what most people advised us to do, we would have put a road straight through our green space and put as many lots as close to the marsh as possible.” But by creating some 20 fewer building sites than the original zoning allowed, the developers not only can sell the 36 they do offer at much higher prices and garner a hefty tax deduction from the land trust, they also avoided the substantial infrastructure, land clearing, and landscaping costs that would have come with higher density. In addition, their permeable roadways don’t require costly drainage piping or the creation and maintenance of retention ponds for runoff. These design decisions seemed right to developers Bayard and Wadsworth, but they admit to enjoying the reassurance of research.

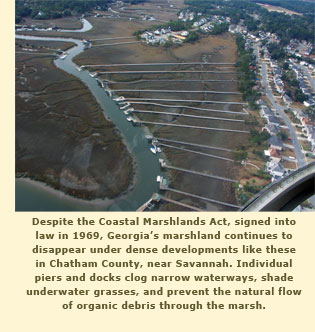

Another issue associated with coastal development is the proliferation of personal docks, which can compromise marsh ecosystems. According to Kriesel and Mullen, these amenities are in fact bad investments. While having water access can add $80,000 or more to the sales price of a home in Chatham County, they were surprised to find that actually building a dock across the marsh to take advantage of that access adds only about $24,000 in value. “They’re like swimming pools,” says Kriesel, “expensive to put in, high-maintenance, and high-liability—and you’re not going to get your money back.” Community docks, by contrast, cause less environmental damage and offer better value to the homeowner. Here, again, economic criteria and environmental good sense are in sync.

Another issue associated with coastal development is the proliferation of personal docks, which can compromise marsh ecosystems. According to Kriesel and Mullen, these amenities are in fact bad investments. While having water access can add $80,000 or more to the sales price of a home in Chatham County, they were surprised to find that actually building a dock across the marsh to take advantage of that access adds only about $24,000 in value. “They’re like swimming pools,” says Kriesel, “expensive to put in, high-maintenance, and high-liability—and you’re not going to get your money back.” Community docks, by contrast, cause less environmental damage and offer better value to the homeowner. Here, again, economic criteria and environmental good sense are in sync.

Georgia Sea Grant director Charles S. Hopkinson says that funding the UGA study was just his organization’s first step—the next one is communicating its results. “Certainly we’ll always need regulatory oversight to protect sensitive marsh environments,” said Hopkinson. “But where regulatory efforts can take years and generate lots of red tape, markets are efficient and can turn on a dime. At the rate the Georgia coast is developing, we need to make sure this information gets fed back into the market as soon as possible.”

For more information about this study, contact Warren Kriesel at: wkriesel@agecon.uga.edu; for more information about the sustainable development at Barbour Pointe, contact Gregg Bayard at: gregg@parallelhousing.org or visit the Barbour Point web site at: www.barbourpointe.com

(David Bryant is Public Relations Coordinator for the Georgia Sea Grant Program).

|