The University's Rainmakers

An in-house team of experts helps UGA researchers

commercialize their work, generating revenue that’s reinvested in research

UGA’s Technology Commericialization Office: (Front L to R) – Kay Janney, Sohail Malik, Rachael Widener, (Second row) – Derek Eberhart, Jessica Orbock, (Third row L to R) – Kim Fleming, (Fourth row L to R) – Shelley Fincher, Terence McElwee, (Last row L to R) – Deanna Wood, Gennaro Gama, Angela Watson, Kathleen Burggraf

For 10 years, Michael Doyle and colleague Tong Zhao had been testing hundreds of compounds in hopes of finding a combination that would kill harmful microbes such as E. coli and salmonella without altering the taste or appearance of food. Their dedication finally paid off in 2008, when they found a combination of two ingredients that did the trick. Individually, they aren’t very strong antimicrobials, said Doyle, who is director of the University of Georgia’s Center for Food Safety, “but add them together and it’s dynamite.”

This antimicrobial wash, which can be used on fruits, vegetables, seeds, meats, and equipment, is just one of hundreds of faculty discoveries or inventions—in fields as divergent as agriculture and medicine—that are available for licensing through the University of Georgia Research Foundation, Inc. (UGARF), a nonprofit organization created 30 years ago to help support the university’s research mission.

Since 1979, UGARF’s Technology Commercialization Office (TCO) has been licensing university innovations to industry for development into commercial products and consequently for public benefit. UGARF holds more than 700 active licenses and, according to the most recent survey conducted by the Association of University Technology Managers, ranks third in the country in total number of license agreements. As a result, UGA received $16.1 million in licensing revenue in 2007, placing it twentieth among colleges and universities nationwide and eleventh among public universities. In 2008, the university’s licensing revenue rose even higher—by some 49 percent—to nearly $24 million.

“We’re very proud of our ranking,” said TCO director Sohail Malik. “It’s a reflection of the quality of research that’s being conducted at the University of Georgia and the partnership between our office, the faculty, and the administration.”

Creations of the Mind

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) defines Intellectual Property (IP) as “creations of the mind: inventions, literary and artistic works, and symbols, names, images, and designs used in commerce.” IP management is a complex, multi-step process that Malik and his team try to simplify for university researchers.

The process starts when a researcher discovers or creates something of significance, generically termed an “invention.” Faculty members fill out an online invention disclosure form that is then evaluated by one of Malik’s licensing specialists. Malik urges faculty who aren’t sure whether they should file a disclosure to contact his office, which he refers to as “their one-stop question-and-answer facility.”

One of his office’s full-time licensing specialists, each of whom has specific areas of expertise and, often, a terminal degree in his or her field, evaluates each discovery to discern two things: whether it is patentable—the list of patentable inventions is long, including therapeutics, devices, software, chemicals, and new and distinct varieties of plants, for example—and whether it has commercial potential. If the answer to both questions is yes, the office will likely apply for a patent.

Malik says it can take anywhere from three to seven years to receive a patent, and it’s costly, too. A U.S. patent costs at least $10,000, a figure that can be significantly higher depending on the complexity of the subject. Gaining worldwide patent protection can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, as each country has its own patent office, legal requirements, and, of course, obligatory paperwork. But such costs should be regarded as investments, because there may also be benefits. “The money we bring in goes back to support research,” Malik said, “and that is particularly important in difficult economic times.”

Once granted, a patent provides the legal protection needed to earn that money. The details of each agreement may vary, but licensing revenue is generally distributed according to UGA’s Intellectual Property Policy, with the first $10,000 of net revenue from an invention going to the inventor. After that, 25 percent goes to the inventor, 10 percent to the inventor’s research program, 10 percent to the inventor’s department or unit, and 55 percent to UGARF, which helps fund promising new research throughout the university.

Scott NeSmith, a professor of horticulture who developed six patented blueberry varieties, says the reinvestment of research funds was critical to the early success of his projects. “We already had strong breeding programs for peanuts, wheat, and soybeans,” he said, “and being able to get money out of that pool really helped us start our blueberry program.”

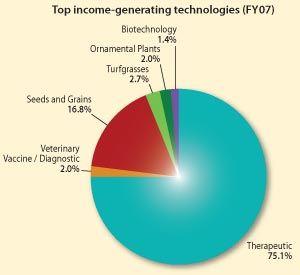

While agriculture has long been a staple of licensing revenue for UGA, revenue is increasingly coming from the life sciences. Malik notes that in 2007 nearly 75 percent of UGARF’s licensing income was derived from therapeutics. Some current examples include Restasis®, a dry-eye treatment developed in the College of Veterinary Medicine; and Clevudine, a hepatitis B drug being marketed as Levovir® in Asia. Levovir®, which was created by Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus David Chu in the College of Pharmacy, is currently in the final stage of clinical trails in the United States. “The FDA approval process is very stringent and time-consuming,” Chu said, “but hopefully the drug will be approved by the end of next year.”

Giving back

Although their revenue figures are a source of pride for Malik and his team, they also promote technologies that generate very little, if any, revenue. “I don’t want people to get the impression that we exist simply to make money,” he said. “We want to make sure that people get the maximum benefit from our inventions. And in some cases that means making technology available for free or very inexpensively under what we call a humanitarian license."

One such technology is the Student Accommodation Management System developed by the UGA Alternative Media Access Center. The software and Web-based system predicts the needs of students with disabilities and notifies departments that will have contact with them of the accommodations required for effective learning. After a visually impaired student registers for classes, for example, the system alerts the specific departments that books in Braille might be needed.

Another humanitarian technology is a nutcracker developed by William Kisaalita, a professor of biological and agricultural engineering. The hand-operated device is specifically designed to help women in Morocco safely and efficiently extract the kernel of the argan nut, which produces edible oil that is essential to their livelihoods. Before Kisaalita’s device was invented, the women cracked the nuts, among the hardest in the world, by hand between two stones—a tedious process that carried the risk of broken fingers and, as a result, loss of vital income.

Other UGA technologies that aid the developing world under humanitarian licenses include a fast early-stage diagnostic test for Chagas disease, a potentially deadly parasitic infection common in Central and South America, and a variety of alfalfa that is particularly suited to the soils of South Africa.

Reaching out and looking forward

Malik and his colleagues often speak at departmental gatherings across campus and meet with individual faculty members to inform them on how the intellectual-property management process works and how the TCO can help them license and market their work. Despite such outreach efforts, some misconceptions remain. The most common, says Senior Technology Manager Gennaro Gama, is that the office will ask a researcher to delay publication of a finding or even avoid publication altogether. While Gama acknowledges that he and his colleagues encourage the seeking of patent protection early on—in order to maximize licensing opportunities—they also recognize that publication is vital to the sharing of knowledge and to the promotion and tenure processes. “In academic life the motto is publish or perish,” he said. “Nobody says patent or perish!”

“In academic life the motto is publish or perish. Nobody says patent or perish!”

Patents generally expire 20 years after the filing date. Once they do, competition from generic drugs and other competitors can quickly eat into revenues. But by diversifying UGARF’s portfolio, heavily marketing faculty inventions, encouraging new disclosures, and reinvesting funds in new research, Malik and his team strive to keep their annual revenue on an upward trajectory. He travels frequently to conferences and trade shows to promote UGA innovations, noting that the university will be well represented at the upcoming BIO International Conference, which this year will be held in Atlanta May 18–21. More than 20,000 business leaders and industry experts are expected at the event, which is the biotech industry’s largest.

“In effect, we are spokespeople for the university, telling the rest of the world about the great and diverse research work going on here and the inventions and discoveries that come out of it,” Malik said, cheerfully adding, “this is one of the best parts of my job.”

Learn more at: www.ovpr.uga.edu/tco.

|