Dealing With Addiction

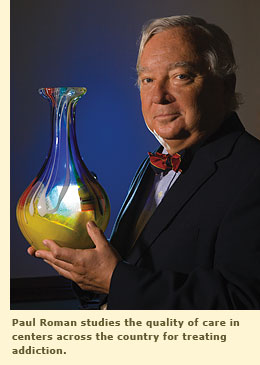

Paul M. Roman, a sociologist in UGA's Institute for Behavioral Research, has played an influential role in raising the quality of care in centers for treating addiction. For the past 25 years he has not only been chronicling how therapies for drug and alcohol abuse have developed and changed, but he also has been nudging centers to improve their care of patients. Along the way, he has managed to mentor a cadre of young professionals to advance the application of research in addiction treatment.

Paul M. Roman, a sociologist in UGA's Institute for Behavioral Research, has played an influential role in raising the quality of care in centers for treating addiction. For the past 25 years he has not only been chronicling how therapies for drug and alcohol abuse have developed and changed, but he also has been nudging centers to improve their care of patients. Along the way, he has managed to mentor a cadre of young professionals to advance the application of research in addiction treatment.

"I'm very impressed with Paul's ability to find, engage, and retain such a good corps of investigators," said long-time friend and colleague Tom McClellan, CEO of the Treatment Research Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. "The UGA group is really making a mark on this field."

Spend an hour with Roman and you'll understand why people flock to him. Funny, self-effacing, and energetic, he exhibits a restless curiosity beyond his area of expertise. He can talk about John Updike, historic houses, and 20th-century American literature as easily as he can about the worldwide history of drug abuse. His Barrow Hall office holds not only a small library but also the evidence of his own addiction: shelves full of art glass bought on eBay.

Roman has been studying treatment facilities as health-care organizations, trying to determine what they do, why they do it, and why they don't pursue alternatives that might better serve their patients. These efforts have been extensive and long-term. Since 1986, his various projects have brought $29 million in public and private grants to UGA.

Early in his career and based at Tulane University, Roman became the country's leading authority on employee-assistance programs (EAPs). The guidelines in his publication "EAP Core Technology" became the industry standard.

This expertise, peers say, helped Roman when he decided to turn his attention to 1,200 treatment facilities across the country in a long-term study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health.

"Paul had had corporate experience with the EAPs, so he could ask what treatment centers were doing as corporations," said Dennis McCarty of the Oregon Health and Science University. "He and his colleagues have given us a perspective that's increasingly important. Treatment organizations and the way they deliver services have as much impact on outcomes as the patient does."

Roman, who is now a Distinguished Research Professor at UGA, has learned some centers follow long-time practices that seem to ignore scientific breakthroughs in overcoming drug addiction. "What people get in treatment is basically what they have always gotten, which is group therapy with a smattering of individualized treatment," said Roman, who directs UGA's Center for Research on Behavioral Health and Human Services Delivery. "One of our challenges is to figure out why agencies have ignored treatment innovations."

Roman, who is now a Distinguished Research Professor at UGA, has learned some centers follow long-time practices that seem to ignore scientific breakthroughs in overcoming drug addiction. "What people get in treatment is basically what they have always gotten, which is group therapy with a smattering of individualized treatment," said Roman, who directs UGA's Center for Research on Behavioral Health and Human Services Delivery. "One of our challenges is to figure out why agencies have ignored treatment innovations."

One reason, he has learned, is the rigid commitment to the 12-step approach, used in Alcoholics Anonymous, in which abstinence is the only outcome and fear of failure is the motivation. The addicted person is effectively beaten down and then built back up, "and it can't work for everyone," said Roman.

Some therapists embrace an alternate method, called motivation-enhancement therapy, developed by William R. Miller at the University of New Mexico. This is a much less negative and confrontational approach. The addicted person forms a relationship with a counselor who learns what's valuable to that person. The counselor emphasizes how not drinking or not using drugs will produce rewards such as renewed relationships with family members. About half the treatment centers in the NIDA study have tried this motivational approach, Roman says, and about 25 percent of them have fully implemented it.

Another reason why treatment centers don't embrace innovation, Roman has found, is that there is a high turnover in the counselor work force. People don't stay long enough in their jobs to feel comfortable embracing something new, or they don't understand the culture of their workplace. Roman is part of a UGA team, headed by psychologist Lillian Eby, investigating what role mentoring plays in workforce retention.

The third prevalent reason for not trying some new measures is that many centers are under-funded. There are few resources for training personnel or for supporting innovations. And there's not enough money to employ the specialized staff needed if a center is going to use new medications as part of patients' treatments (see Covering the Cost of Treatment).

Roman's NIDA study has not only helped identify these and other reasons why some clinics have been slow to use new and more effective medications for treating addiction; it has also pinpointed some of the factors that facilitate their adoption, said Thomas Hilton, a grants administrator with the National Institutes of Health. It has to do with what Roman calls a center's "absorptive capacity," its ability to soak up new knowledge and put it into practice. Generally, larger organizations have more absorptive capacities. They have more staff, which usually means a more diverse staff, in terms of education and discipline, "so you might have people with PhDs who are up on the literature and who make suggestions about new innovations," Hilton said.

Another method of treatment Roman has studied is the therapeutic community (TC) approach. This offers a long-term setting where people learn "a whole new way of living, with a full-scale socialization," he said. "They may stay two years or more, with therapy 24 hours a day. Therapeutic communities are where the phrase 'tough love' originated."

Hilton said Roman's work "has supported revolutionary changes in TC therapeutic and business practices nationally." One change is that many such communities now allow residents to receive pharmacotherapy, both for addiction and co-occurring psychiatric conditions. TC communities have traditionally been drug-free. People taking methodone, for example, instead of heroin, or people needing prescription drugs for depression weren't allowed to take their medications. Today some of these communities have softened their positions, Hilton said.

Roman's findings have resulted in the restructuring of some of the largest therapeutic communities to better accommodate innovative treatment approaches. Some TC's are now considering offering out-patient day treatment as opposed to residential treatment. They are affiliating with vocational rehabilitation programs so that patients can acquire job skills. Leaving the TC setting, for any reason, was unheard of years ago.

All of this "is a radical turnaround from just a decade ago," said Hilton. "Now that addiction is being viewed as a problem nationally, there's pressure on all providers to reconsider what they're doing and to incorporate more mainstream medical and mental health approaches. Paul's findings have helped jumpstart the rethinking of many practices."

(Rebecca McCarthy is on staff with the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. She wrote about terrorism in the winter 2008 issue of ugaresearch).

|