Tracking the Teachers

by Catherine Gianaro

![]()

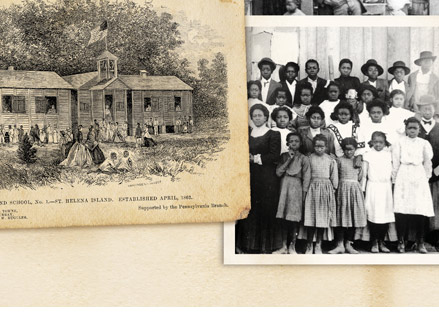

A Powerful Legacy for Black Education

Traditional scholarship on post-Civil War education in the southern United States has assumed that the North led the initiative to provide formal education to the freed people. Historians have long held that the teachers in the early southern black schools were primarily young, white, schoolmarms from New England.Not so, according to University of Georgia historian Ron Butchart. His extensive archival work for his extended project, “A Freed People’s Education: Learners, Classrooms and Teachers,” has yielded altogether different findings.

The most obvious finding, Butchart points out, is that the Yankee schoolmarm — the northern female schoolteacher — wasn’t as ubiquitous as she has been portrayed in the past seventy years of scholarship. Butchart discovered that virtually half of the teachers were southern, and among those individuals, most of those were white men.

Another surprising trend, he discovered, was the strong presence of African Americans among northern and southern teachers alike. “Northern black teachers were disproportionately represented among all northern teachers,” he said. “And among southern teachers, the number of black teachers was simply astounding.”

During the 19th century, it was difficult for northern African Americans to get a good education, and nearly every state of the slave-holding south outlawed education for African Americans altogether. However, there was a tradition, begun in the slave community, of surreptitiously passing on literacy; freed blacks had a little more access to literacy, but not much.

“Yet we had two to three thousand southern teachers who were African American. And when you read their letters, you see they were perfectly literate,” Butchart said.

Historians estimate a 5 percent literacy rate among southern blacks during that time. “Whether a very high proportion of that group ended up teaching, or whether southern black literacy was more prevalent than scholars realized, we don’t know yet,” he said.

However, in terms of sheer numbers, the majority of teachers in the South at that time were southern white men. “I think it was a matter of being driven by ‘I have to get work. I have to do something to get bread on the table,’” said Butchart. “By the late 1860s, there had been a succession of serious crop failures in the South, so things were really quite desperate.”

For some of them, teaching was also a “defensive” stance. “They wanted to make sure that southerners, rather than northerners, educated the freedmen because they wanted to control the kinds of ideas that their former slaves were exposed to,” he explained. “Some of them said so quite explicitly.”

But that’s not the whole story. Butchart observed that some white southerners seemed to take a genuine interest in African-American education. “They were among a handful of very interesting people who said, ‘Look, the world has changed. The social relations of the past can no longer hold. These people deserve an education, too.’ And they provided it.”

Still, the image of white northern women devoting themselves to black education in the Reconstruction-Era South is not without some basis. For example, Carolyn Putnam, who created the Holley School (named after her life partner, Sallie Holley) spent 49 years of her life in the South and died in Lottsburg, Va., where a monument, erected by the town’s black community, still stands in her honor. She was one of a few dozen northern white women who dedicated their lives to southern black freedom.

Northern white single women had few chances to use their executive abilities in the 19th century, Butchart said, so they moved to the South, where they could establish schools, raise funds, teach, and administer their own schools, while acting on their sense of social justice.

-CG

For comments or for information please e-mail: rcomm@uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()