by Judy Bolyard Purdy

Intro

| Tangible results | Cows,

cows & more cows

|

Genetic preservation | Pig

Tales

| The war against disease

Intro

This isn’t the first time that advances in technology have led some to question whether scientists are playing God. But in the case of cloning, which inherently involves the very building blocks of life, perhaps such accusations were inevitable.

Steve Stice sees it differently.

“There’s a lot of concern that we’re producing monsters,” said Stice, a University of Georgia professor of animal and dairy science and one of the early pioneers in cloning research. “Nothing could be farther from the truth.

“I say we’re doing what Mother Nature allows us to do,” he said. “I try to get others to understand where I think cloning fits in.”

In Stice’s view, it fits squarely into the fields of agriculture and medicine, a tool to be used to produce more and higher-quality food and to manufacture cures in the war against disease.

Where it does not fit, he said, is in people. “I think cloning people is dangerous,” Stice said. “I don’t think it should be done. It’s morally repugnant to me.”

Since joining the UGA faculty almost four year ago, Stice has applied for six patents — four on cloning technology and two on developing stem cells into nerve cells. He already holds the first U.S. cloning patent, which is based on technology he helped develop a decade before the birth of Dolly, the sheep that became the first mammal cloned from an adult cell.

“I knew from the start the potential of cloning, what it could do some day. And I knew that stem cells had great potential,” he said. “Really the thing that drives me is seeing what these technologies can do in the real world. I’d like to take basic technology and move it into applications so people can use it.”

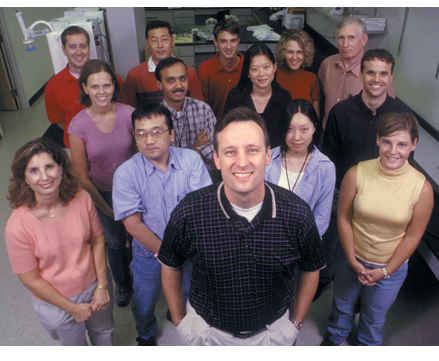

Cloning pioneer Steve Stice and his University of Georgia research team.

Farm, "pharm" and medicine

Perhaps the most rapidly developing applications are in agriculture. Stice wants to improve the efficiency and speed of livestock cloning as well as use cloning to preserve and multiply genetically superior animals. He envisions the day when cloning will be a fast, efficient and economically feasible breeding option for cattle, hogs and other livestock.

Compared with conventional breeding methods, clones can more accurately be endowed with specific genetic traits — for instance, tender, well-marbled meat or faster, more efficient muscle growth. Cloning also holds promise for conferring genetic resistance to livestock diseases.

“We hope to breed cattle that lack the gene or genes that make them susceptible to mad cow disease,” Stice said. “In the future we’ll be able to take cells from the very best animal and then improve upon them with genetic modifications — either knocking out deleterious genes or adding favorable genes.”

In addition to cloning farm animals, Stice wants to build on his earlier success of cloning “pharm” animals that could supply an abundance of medically important proteins.

Stice was a founder and the chief scientific officer at Advanced Cell Technology, the company that cloned the first cattle, George and Charlie, in 1997, just 11 months after Dolly made her debut. The calves opened the door not only to large-scale cloning of genetically engineered farm animals but also to the possibilities of cloning pharm animals. George and Charlie earned Stice two patents — one for cattle cloning from adult cells and one for transgenic technology, which enables genes to be transferred from one organism to another. International headlines touting the Holsteins’ arrival were short-lived. “The Monica Lewinski story broke two days later,” Stice said with a wry smile.

On the medical front, Stice’s UGA research is breaking new ground in the realm of human embryonic stem cells. These cells hold the potential to differentiate into all the various tissues in the human body. Growing specific tissues from these master cells could pave the way for a host of new medical treatments, such as nerve cells for Parkinson’s disease, and bioengineered materials that meld human cells with artificial platforms for such things as cardiovascular bypass surgery.

Since joining UGA’s faculty, Stice has helped pioneer culture techniques for growing both primate and human embryonic stem cells for medical applications. In collaboration with the Athens-based biotech firm BresaGen Inc., the researchers are among a handful worldwide that received NIH approval to grow human embryonic stem cells for federally funded research. The UGA-BresaGen collaboration holds four of the 78 approved cell lines eligible for NIH research funds following President Bush’s August 2001 decision to permit federal money to support limited research in this area.

Intro

| Tangible results | Cows,

cows & more cows

|

Genetic preservation | Pig

Tales

| The war against disease

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()