by Judy Bolyard Purdy

Intro

| Tangible

results | Cows,

cows & more cows

|

Genetic preservation | Pig

Tales

| The

war against disease

Genetic preservation

A lesser-known benefit of the UGA cloning research is its potential to help scientists preserve genetic variability among livestock and endangered animals — much the same way as gardeners save legacy vegetable seeds.

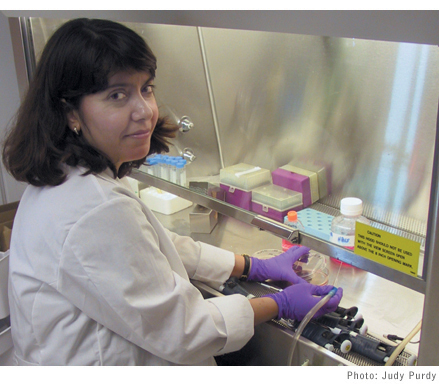

Sezen Arat, a veterinarian and reproductive disease specialist, spent two years as a visiting scientist in Stice’s lab learning the cloning process and developing technology to enhance genetic engineering. She plans to use cloning to help preserve the genetic diversity of Anatolian cattle in her native Turkey. The breed is well-adapted to Turkey’s environment but it holds limited economic or scientific interest for the rest of the world. As a result, Arat sees cloning as a way to help preserve the diminishing population that one day could disappear.

“We have some original Anatolian cows that are small but they are very strong against the environment and cold weather,” said Arat, who received a World Bank fellowship to help finance her UGA work. “We could lose our own genotype of cattle. I want to have the tissue samples so we can clone these animals and again produce the same genotype or we can keep the samples and clone them later.”

While at UGA, Arat helped develop some of the efficiency that led to cloning those first eight calves. She also contributed to developing technology that uses a marker gene — one that produces a green fluorescent protein — to verify that specific altered genes were passed on to cloned offspring. The procedure is a critical step in the long-term effort to develop transgenic livestock with, for example, disease resistance.

Arat also contributed to preliminary research on developing a universal recipient egg cell, or oocyte, that could be used to clone a variety of livestock animals or endangered species. The research also will lead to a more complete knowledge of the signals that occur between the transferred genetic material and its new cell host.

Sezen Arat plans to use cloning technology to preserve a rare breed of cattle in her homeland of Turkey.

“If we can understand this relationship, maybe we can use bovine oocytes as a universal recipient to clone other kinds of animals,” including endangered species, she said.

Stice would like to try his hand at cloning endangered species, but not everyone likes the idea.

“There’s quite a bit of interest in cloning to save endangered species, but I get the most resistance to the idea from conservation groups, which are concerned about losing genetic diversity,” he said. In a counter-intuitive way, cloning actually could preserve the diversity, Stice said.

“With smaller habitats you get isolated populations of animals and then they become inbred. That’s why the Florida panther may have problems reproducing,” he said. “Cloning may be useful in introducing new genetics from a different population somewhere else.”

In January 2001, scientists at Advanced Cell Technology, a company Stice co-founded in 1994 with his doctoral adviser, James Robl, cloned an endangered wild ox or gaur. Noah, the first endangered animal to be cloned, died two days after birth from an opportunistic infection.

Intro

| Tangible

results | Cows,

cows & more cows

|

Genetic preservation | Pig

Tales

| The war against disease

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()