by Judy Bolyard Purdy

Intro

| Tangible

results | Cows,

cows & more cows

|

Genetic preservation | Pig

Tales

| The war against disease

The war against disease

Animal cloning is a natural complement to Stice’s other research: nudging embryonic stem cells down specific developmental pathways for medical applications.

The microscopic cells derive their great therapeutic potential from an almost magical ability to transform into all 220 or so types of the body’s tissues and cells.

Together, UGA and BresaGen are helping unravel mysteries of getting stem cells to produce specific cell types.

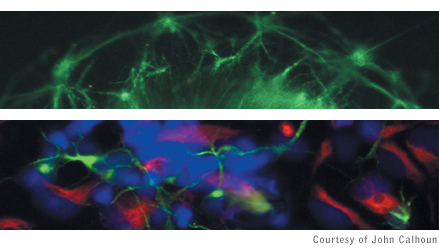

Embryonic stem cells from rhesus monkeys form a network of nerve cells (above top) using the techniques pioneered by UGA-BresaGen researchers. On bottom, nerve precursors (red) and nerve cells (green) grown from stem cells offer new hope for treating Parkinson’s disease.

“Once you get the stem cells growing, they’re easy to maintain,” said John Calhoun, a doctoral student who helped develop stem cell culture techniques.

With some routine “gardening” a culture will grow and grow and grow, almost in perpetuity, he said. The hard part is getting them to develop into nerve, muscle or artery cells, for instance.

Such knowledge is a first step in developing replacement therapies for diseases involving loss of particular cells, such as nerve cells in Parkinson’s disease. It also holds promise for engineering surgical replacement parts.

“We’re not looking at developing an organ,” Calhoun said. “We’re learning about the signals that stop and start the differentiation that occurs during development.”

Long-term, Stice wants to develop specific nerve cells, called neural stem cells, for alleviating Parkinson’s symptoms.

When nerve cells in certain brain regions of a Parkinson’s patient begin degenerating and dying, they stop producing dopamine, a signal transmitter critical in relaying nerve messages within the brain. Once 60 to 80 percent of the dopamine-producing cells have died, a patient begins to show the characteristic tremors, slowed movement and other symptoms of this incurable and eventually fatal disease.

Stice collaborates with researchers at other universities who already have shown that implanting nerve stem cells into specific brain regions of a Parkinson’s patient may reduce symptoms and restore functions lost to nerve cell degeneration.

“One of our collaborator’s patients was able to run out of the World Trade Center on September 11th and get to a train station,” Calhoun said.

Stice knows there’s still much work ahead. “We’re about two years away from human trials with the Parkinson’s research,” he said.

In the meantime, the UGA and BresaGen teams are pushing ahead on animal model studies for the disease and making uniform, functional dopamine-producing cells that mimic those in the human body.

“There’s a lot in making nerve cells that goes beyond dopamine,” Stice said. “We need to do functional tests — does the cell in a petri dish function like a dopamine-producing cell in the brain?”

Nobody knows yet. But the UGA-BresaGen collaborators are finding out by using a special rat model lacking dopamine-producing cells in specific areas of the brain. Rat behavior undergoes pronounced changes when neuron stem cells are introduced into specific brain regions.

“We know the process works and the test is reliable. It’s a long-term study and will take time to pinpoint the specific cell development conditions to obtain appropriate renewed brain function,” said Clifton Baile, another GRA Eminent Scholar at the university who oversees the behavioral tests. Baile, who is ProLinia’s CEO and board chairman, played a key role in recruiting Stice to UGA.

“If we found a cell type to cure Parkinson’s in rat, the next step would be to induce Parkinson’s-like symptoms in primates and look for the same kinds of effects,” said Ian Lyons, who directs BresaGen’s part of the stem cell research. “It’s an exciting part of biology to be in.”

And so is Stice’s other stem cell research with Robert Nerem’s team at the Georgia Institute of Technology, which focuses on cardiovascular applications of stem cells. In this project, Stice is developing endothelial cells from embryonic stem cells and also working on ways to bypass rejection issues.

Endothelial cells line the blood vessels. The Ga. Tech-UGA research group wants to use those cells to engineer tissue for such applications as cardiac bypass surgery or other vascular replacements, he said.

Of cloning and stem cell research programs, Stice sees the latter as having greater healthcare applications.

“It can be used in so many different ways to benefit people and that will be very important,” he said.

But for all his success so far, Stice said he believes the most important discovery of his career “is yet to come.”

“I hope I can help a student make a basic discovery,” he said, “on how cells determine what to become — for example, a nerve cell instead of a muscle cell — thus benefiting both animal cloning and cell therapies.”

For more information, access Stice’s Web site http://www.uga.edu/caes/biotech/stice.html, ProLinia’s Website www.prolinia.com, or BresaGen’s Web site www.bresagen.com

Judy Bolyard Purdy is the University of Georgia’s director of research communications. She has degrees in biology, botany and journalism and has won several regional and national awards for writing.

Editor’s Note: The Learning Channel will feature Dr. Stice’s work in its upcoming program, Ten Ultimate Technological Inventions of the 1900s.

Intro

| Tangible

results | Cows,

cows & more cows

|

Genetic preservation | Pig

Tales

| The war against disease

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()