How

a Slime Mold

Came to the Aid of

Alzheimer's Research

by Kathleen Cason

Intro/Proteins

run amuck

| The path to hirano bodies

Serendipity and beyond

|

What's ahead

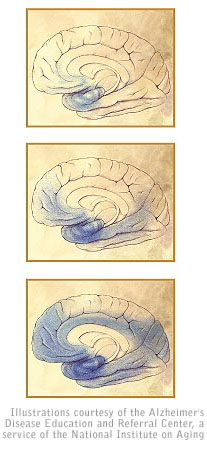

(Top) Ten to 20 years before any indication of Alzheimerís disease

is evident, the brainís memory centers begin to shrink.

(Middle) As the damage spreads, an otherwise healthy person experiences

impaired memory, language and thinking.

(Bottom) During the final stages of Alzheimerís disease, brain

atrophy is widespread and patients no longer recognize loved ones nor

have the ability to communicate.

For more information about Alzheimerís disease, log on to www.alzheimers.org

Blue shading indicates affected regions of the brain at various stages of

Alzheimerís disease: preclinical (top), mild or moderate (middle) and severe

symptoms (bottom).

Intro

In an ancient Persian fable, three princes from the kingdom of Serendip go out into the world to gain experience. During their adventures, they find they have a gift for making unexpected discoveries.

Like those fabled princes, UGA cell biologist Marcus Fechheimer and his research team have discovered they too have a gift for serendipity.

In the course of trying to understand how proteins “know” where to go in a cell, the researchers unexpectedly stumbled upon an unusual cellular structure normally associated with Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases.

“We didn’t expect to find a structure in a slime mold that

is present in increased amounts in people with Alzheimer’s —

particularly present in the brain’s major site of learning and memory.

That’s where these things accumulate,” he said.

Fechheimer’s team not only chanced upon this unusual structure —

called a Hirano body — in a slime mold but also figured out how to

force cells to produce them on command in the laboratory. Up till now,

these structures could only be studied in brain tissue of people who had

died. Because of this discovery, scientists will be able to study Hirano

bodies in living cells for the first time and unravel the mysteries of

this little-understood protein deposit.

Though Hirano bodies are common in the brains of people diagnosed with

dementia, their role in disease, if any, is unclear.

“We don’t know if a Hirano body is good or bad or why it’s

there or how it forms,” said Ruth Furukawa, a UGA research scientist

who co-directs the study.

Proteins run amuck What causes neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s is still

largely unknown, but something destroys nerve cells in the brain over

a period of time as victims gradually lose their minds.

In the hunt for cause and cure, scientists have focused on various abnormal

protein deposits that mar diseased brains. Deposits called plaques and

tangles have captured the most attention. Hirano bodies, while not at

the forefront of Alzheimer’s research, are another type of protein

deposit associated with the disease.

“Hirano bodies are certainly more prevalent in brains from patients

who are suffering from dementias, probably any type,” said James

Bamburg, one of Fechheimer’s collaborators and a professor of biochemistry

and molecular biology at Colorado State University. “Hirano bodies

also occur in brains of individuals with normal cognitive function but

usually increase in number with age.”

Nearly four decades have passed since Asao Hirano, an eminent neuropathologist

at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, first discovered the peculiar

deposit in the brain’s memory center. Since then Hirano bodies have

been reported in the brains of people with neurodegenerative diseases,

as well as diabetes, stroke and alcoholism.

“Making a Hirano body may be a cellular mechanism for dealing with

run-amuck proteins,” said Furukawa, who manages the day-to-day operation

of the lab. “That’s just a hypothesis.”

Run-amuck proteins certainly seem to play some role in all the diseases

where Hirano bodies are found.

“Perhaps Hirano bodies do nothing; perhaps they’re part of

cell death; or perhaps they are adaptations to stress that are good for

cells,” Fechheimer said. “Because they’re seen in so many

diseases, it’s worth finding out.”

After more than 20 years probing basic questions in cell biology, Fechheimer’s

team is well positioned to explore the role of Hirano bodies in cells

and in human disease.

“I didn’t think we were working on anything that had to do

with Alzheimer’s disease,” said Fechheimer, who uses a slime

mold as his lab’s version of a “guinea pig.”

Intro/Proteins

run amuck

| The path to hirano bodies

Serendipity and beyond | What's

ahead

For comments or for information please e-mail the editor: jbp@ovpr.uga.edu

To contact the webmaster please email: ovprweb@uga.edu

![]()